Vol. III, No. 1

It was suggested to me by a friend that the uBlog series "Four on the First," a monthly presentation of four albums I own or might have recently enjoyed, now having run two years, might be made richer with brief reviews done retroactively. In fact, I had been weighing the idea myself and, upon the request from a trusted member of my little audience, prepared to begin at the start of 2006. Around the first of every month, now, each album of Volumes I and II will be addressed in turn. I won't be publishing any new sets; there is no need. Volumes III and IV will return us to a library of eight dozen musical works — and give me time to discover some new pop music, since I had nearly run out.

Drawn from Life, Brian Eno (2001) — Inimitable and indefatigable, Brian Peter George St. Jean le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (known more economically as Brian Eno) collaborated with Peter Schwalm on this addition to his two-decade ambient and electronic oeuvre. The album is predominantly minor-key and while not quite dark, Eno and Schwalm's arrangements and production are melancholy. Legato synthesizer leads settle into downtempo drum loops that, with a nod to trip-hop, match subsonic pulses with doctored snares and glossy rhythm sequences.

Drawn from Life, Brian Eno (2001) — Inimitable and indefatigable, Brian Peter George St. Jean le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (known more economically as Brian Eno) collaborated with Peter Schwalm on this addition to his two-decade ambient and electronic oeuvre. The album is predominantly minor-key and while not quite dark, Eno and Schwalm's arrangements and production are melancholy. Legato synthesizer leads settle into downtempo drum loops that, with a nod to trip-hop, match subsonic pulses with doctored snares and glossy rhythm sequences.

Track four, "Like Pictures Part #2," is the album's catchy standout; over a trudging, exotic beat with off-time handclaps can be heard digitally stretched vocals of 1980s multimedia postmodern pop doyenne Laurie Andersen. Andersen's lyrics are as laconic as they are whimsical, the stage artist once again having fun at ontology's expense. Like her or not, Andersen is singularly intelligible; contra pitch-bent gibberish on sixth track "Rising Dust," toddler babble on ninth track "Bloom" and vocoded chorus on tenth track "Two Voices." For its part, "Bloom" is the most immediately faithful to Eno's thesis, a calm exchange between man and child recorded in a kitchen or family room to the effusive serenade of a string ensemble, the seven-minute piece kept in time by a cardiac thump and its reverse set end-to-end.

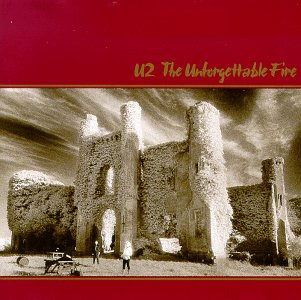

The Unforgettable Fire, U2 (1984) — What happens when Brian Eno is obligated by contract to direct the creation of an album by a rock band approaching mega-stardom? Said band is never the same again. After three records by producer Steve Lillywhite in as many years, U2 had moved from precocious garage rock to devotional garage rock to political garage rock; with Daniel Lanois, Eno set up with the Irish quartet in Ireland's Slane Castle and rolled tape, cultivating the rapport and compositional inspiration responsible for the 1987 éclat The Joshua Tree and what casual fans would thereafter insist as prerequisite for a "U2 song."

The Unforgettable Fire, U2 (1984) — What happens when Brian Eno is obligated by contract to direct the creation of an album by a rock band approaching mega-stardom? Said band is never the same again. After three records by producer Steve Lillywhite in as many years, U2 had moved from precocious garage rock to devotional garage rock to political garage rock; with Daniel Lanois, Eno set up with the Irish quartet in Ireland's Slane Castle and rolled tape, cultivating the rapport and compositional inspiration responsible for the 1987 éclat The Joshua Tree and what casual fans would thereafter insist as prerequisite for a "U2 song."

It was in Slane that Dave "Edge" Evans transmuted the sound of two electric guitar strings fingered at perfect fourths and fifths with syncopated delay into a categorical style; that Larry Mullen, Jr. used rack toms as high-hats; that Adam Clayton began to sublimate his bass performances into loyal, deep-toned chord roots and passing tones; and that Paul "Bono" Hewson found another half-octave to his vocal range. But for singles "Pride" and "Bad," the album is a lesson in the limits of experimentation according to schedule and budget; it is rough and uneven. Still, it is an achievement and a favorite.

Phases of the Moon, CBS Records/The China Record Company (1981) — As a remedy for those of us who once believed Chinese folk music consisted of clumsy twangs set at parallel fifths, CBS Records' Earl Price assembled recordings of music performed by Communist China’s Central Broadcasting Traditional Instruments Orchestra and published the collection under the title Phases of the Moon. A compendium of traditional music, Phases traverses the country and its history, setting 20th Century compositions alongside melodies from Xinjiang and Yunnan provinces; presenting a motif from the Peking Opera, borrowing from the Uygurs and Mongols. The compact disc's booklet includes a narrative by Price, a poem by Bo Juyi, documentation for each song from the China Record Company and ink drawings of native instruments.

Phases of the Moon, CBS Records/The China Record Company (1981) — As a remedy for those of us who once believed Chinese folk music consisted of clumsy twangs set at parallel fifths, CBS Records' Earl Price assembled recordings of music performed by Communist China’s Central Broadcasting Traditional Instruments Orchestra and published the collection under the title Phases of the Moon. A compendium of traditional music, Phases traverses the country and its history, setting 20th Century compositions alongside melodies from Xinjiang and Yunnan provinces; presenting a motif from the Peking Opera, borrowing from the Uygurs and Mongols. The compact disc's booklet includes a narrative by Price, a poem by Bo Juyi, documentation for each song from the China Record Company and ink drawings of native instruments.

Pulled open between nation and culture, however, was the interstice through which Price allowed politics to enter. Days of Emancipation, a rapturous anthem led by a virtuoso, double-reeded suona, is so rousing that listeners will need to remind themselves that it is no less insidious than "Deutschland uber Alles." Days is introduced in the notes as composer Zhu Jianer's 1950 melodic transcription of the "joy and excitement" Chinese farmers were said to have expressed at communization that would leave 30 million dead. One can't help but imagine, set to this music, a film of serial stills that follow the peripatetic evangelism of the Red Guards to come sixteen years later, leaving for history such wonderful vignettes as a man having the hair shorn from his scalp for the inexpiable offense of styling his coiffure after Chairman Mao's.

Yet because Days of Emancipation enchants as gracefully as a tune from any other century, it should be preserved for a nation truly emancipated, removed from its original purpose, words perhaps added — reclamation by recondition, as Martin Luther did when he seized libationary volkslieder for the church hymnal. Then Chinese music would be not for militarists or communists or another autocratic dynasty, but for the Chinese people themselves.

So, Peter Gabriel (1986) — If you say "Peter Gabriel," most Americans who grew up in the Eighties will respond "Sledgehammer" or "In Your Eyes." These two songs' escalade of singles charts brought commercial permanence to Gabriel who, if not as assiduous as Brian Eno, rivals his fellow Englishman's proclivity for the exotic and eccentric. An audition of So when familiar only with its two vanguard singles — or even the third, "Big Time" — and expecting a horn section or African percussion on every track, may end in surprise. The album is delicate, sparse, bright and synthesized; some might say antiseptic. It invited the talents of a dozen of the day's best recording musicians but employed them fastidiously: Police drummer Steward Copeland is credited with playing high-hat for the opening track "Red Rain." If making an eclecticist radio-ready was the objective, of course, we can say two decades on that So was a surpassing triumph. That Daniel Lanois co-produced the album not two years after an earthy and rugged The Unforgettable Fire attests both his manifold director's temperament and Peter Gabriel's artistic prerogative.

So, Peter Gabriel (1986) — If you say "Peter Gabriel," most Americans who grew up in the Eighties will respond "Sledgehammer" or "In Your Eyes." These two songs' escalade of singles charts brought commercial permanence to Gabriel who, if not as assiduous as Brian Eno, rivals his fellow Englishman's proclivity for the exotic and eccentric. An audition of So when familiar only with its two vanguard singles — or even the third, "Big Time" — and expecting a horn section or African percussion on every track, may end in surprise. The album is delicate, sparse, bright and synthesized; some might say antiseptic. It invited the talents of a dozen of the day's best recording musicians but employed them fastidiously: Police drummer Steward Copeland is credited with playing high-hat for the opening track "Red Rain." If making an eclecticist radio-ready was the objective, of course, we can say two decades on that So was a surpassing triumph. That Daniel Lanois co-produced the album not two years after an earthy and rugged The Unforgettable Fire attests both his manifold director's temperament and Peter Gabriel's artistic prerogative.